K3S on Balena

Balena is a software company that specializes in creating solutions for the IoT space. Their flagship product balenaCloud is a fleet management platform that solves a lot of the pain points in an IoT deployment, namely host OS updates, application deployment workflows, and making scaling more manageable. The cloud product is free for up to 10 devices and a single user, making it suitable for a small home lab, but much of the core technology is also open-sourced as openBalena. In my view the device enrollment workflow is stellar: you download an image specific to your target device platform, flash it on an SD card, and then boot up your device, which automatically registers with the fleet and starts running the target application.

The Balena application/deployment model is quite simple:

- A Fleet is a collection of some devices.

- A device always belongs to exactly one Fleet.

- Every device in a Fleet runs some release of a shared application configuration.

- The application is either expressed as a single Docker container, or a docker-compose environment with multiple containers and potentially storage volumes.

Balena as undercloud

A consequence of the single-application-per-device model is that it is difficult and/or clunky to divide some set of applications across some set of devices, and as such devices can often be underutilized. For example, in a home lab, you may wish to run an IDS, a PiHole, a Plex server, and maybe some other small applications. In the Balena model, you would either have to split each application out, create a Fleet for each, and assign a whole device to each application, or somehow bundle all the applications in a docker-compose environment, using environment variable switches or similar to control which services should be enabled/disabled on a given host device.

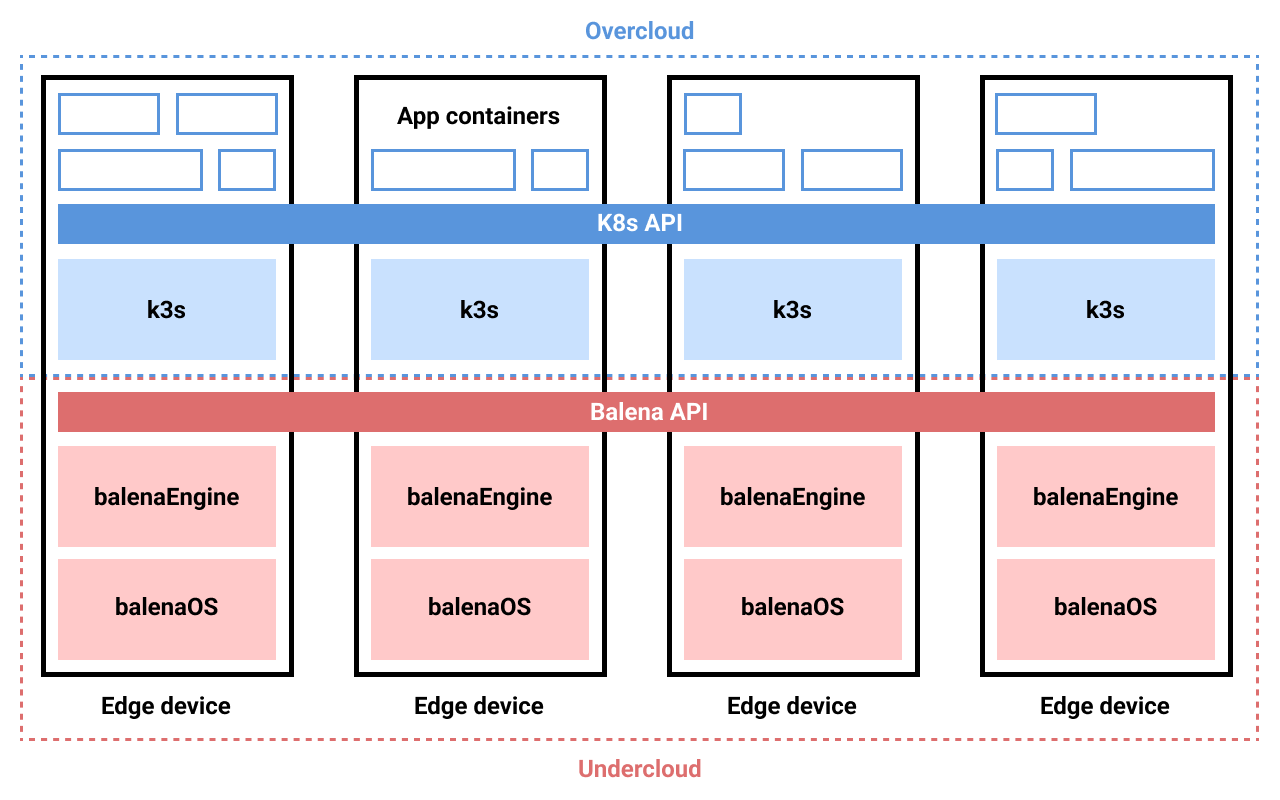

One solution to this problem is to shift the orchestration of applications from Balena to a higher layer, i.e., instead of deploying your target applications directly to Balena, you instead deploy a way to run applications to a single Balena fleet, and then you interact with that system to configure and deploy your target applications. In this architecture, Balena acts as a sort of “undercloud”: you’re using Balena’s cloud platform to bootstrap your own local cloud, combining advantages of each.

I was interested in seeing to what extent this was possible on Balena, and so spent some time evaluating the complexities of packaging something like K8s as a Balena application. The desired end state would be, you can flash all of your devices (Raspberry Pis, Jetson Nanos, etc. – a wide variety of SBCs are supported) with the same base image, and then build one Balena application for your K8S cluster and deploy to all devices simultaneously. Balena will then handle host OS updates for you and any changes you make to the K8S environment (e.g., adding Tailscale integration or something) will be rolled out across the fleet uniformly by default.

Packaging challenges

K3s was the obvious choice for the K8s distribution, as it’s designed specifically with the edge use-case in mind: it has a smaller footprint, uses websockets to tunnel the kubelet API (meaning the kubelet could be running behind several firewalls or NAT layers) and at this point is pretty battle-tested on commodity SBCs such as Raspberry Pi.

Adapting K3s to run on top of Balena was another matter. BalenaOS deploys applications as Docker containers, but it’s not Docker precisely–rather, Balena’s own balenaEngine, which is a fork of moby, the container framework that provides the base for much of Docker itself. So we need to accomplish a few things:

- The K3s control plane (API server) needs to be able to run in a container on Balena Engine.

- Container storage created by K3s should be allocated from outside the K3s container’s overlay file system. I’ll go in to why.

- Any cgroups applied to K3s containers should use the same cgroup manager as BalenaOS. I’ll also go into why this is important.

Besides these challenges, I think it is useful to call out a few non-goals:

- The K3s container should run rootless, i.e., not in “privileged” mode. While this may be simpler to do in the future, it is not feasible at the moment in a container context.

- All possible container configurations will work! This will likely not be the case, as we must run the K3s control plane in a container in order to deploy it via Balena. In particular, any containers running on K3s in privileged mode will have a slightly different view of things than if you were running them on K3s on the host directly. While this may not affect anything in practice, in theory it could.

Let’s look at each challenge individually.

Running K3S in a container

The principle challenge was how to run K3s itself inside a container. There is some prior art on this, namely the K3d project, which helps developers spin up K3s “clusters” as Docker containers. However, because it’s use-case is K3s development, not running production workloads, K3d wants to be in charge of creating and configuring the cluster and its containers, but Balena requires that we specify this explicitly ourselves as part of the docker-compose declaration. Importantly, it’s not possible to add a new node to a cluster. So, it is out, but we can learn some of the requirements of running K3s in a container by examining its source code, where we for instance learn that K3s server/agent containers must be run in privileged mode.

Separately we need to build our container image. One of the nice things about Balena is their tooling for this. With the understanding that you’re trying to build one application for deployment to potentially many different devices, you can express your Dockerfile as a template and use placeholders to specify which base image you are building from for a given target platform. This prevents a lot of boilerplate as the number of supported platforms increases.

Solutions:

- Install K3s in a container image.

- Configure the K3s container to run in privileged mode, mostly so that /dev devices are accessible, both from the K3s control plane and so that they can be passed to pods running on K3s.

- Similarly, configure the container to run in the host networking stack. This helps most CNIs (Container Network Interfaces) to function as normal.

The right filesystem, at the right time

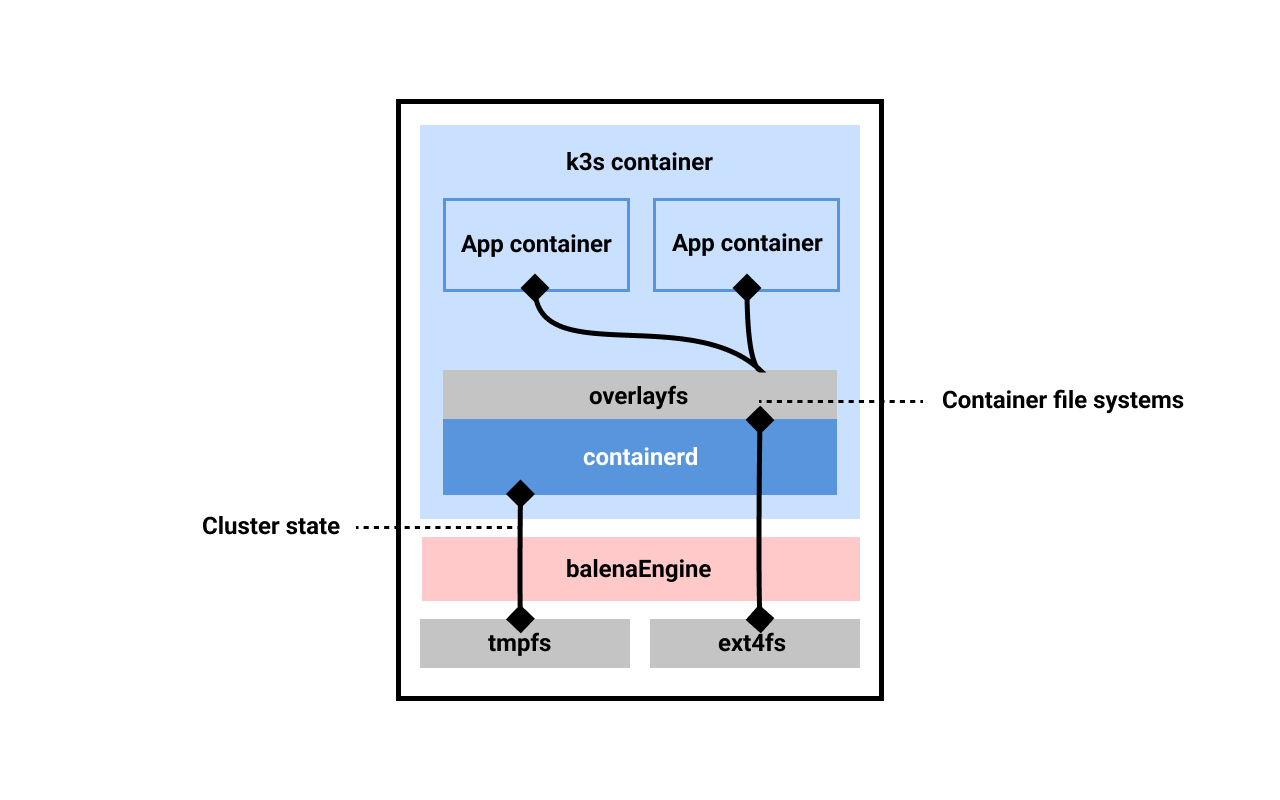

A Docker image consists of layers of deltas applied to the layer below. This is one of the reasons why Docker containers can be quite size efficient if managed well: if several containers share a common ancestor, there is only 1 copy of that ancestor’s layer(s) on disk. However, a consequence of this design is that when a container starts from an image, the container’s filesystem inherits this layering property: any operations done inside the container happen in a new layer (how exactly this works depends on the overlay file system in use.)

The primary implication here is that if your container is doing a lot of i/o against its default overlay filesystem, it will likely either (a) balloon in size over time or (b) perform so many writes/deletes that your storage on-device (likely, SD card) will get hit pretty hard. The reason for this is that edits to any particular file will copy the entire file from the lower layer to the upper layer and then perform the edit; particularly for large files, this can be a problem.

Fortunately, Docker volumes solve this problem by mounting a separate path as a different filesystem. Balena supports allocating Docker volumes and attaching them to your application containers; they will be formated with ext4 (for our purposes, just important that it’s not an overlay filesystem.) Additionally, it is possible to mount tmpfs volumes, which importantly are volumes that exist only in memory and not on disk. This means they are by definition not persisted, but are great for reducing i/o to the underlying storage medium.

So what directories/paths does K3s need to do its work? It turns out there are two main classes: runtime (ephemeral) and data (persistent). The runtime directory is used mostly by the container runtime, in our case containerd. This includes the gRPC sockets as well as a state file that holds information about the running containers; when the k3s container is stopped, all of the spawned container processes will also exit, and they must be re-created. As such, this “state” file can be considered ephemeral as it is ultimately tied to the lifecycle of the kubelet process.

The data directory on the other hand stores all of the persisted about the containers, including container images, volumes, and the containers’ overlay file systems once created. Importantly, the overlay file systems are created from the non-overlay Docker volume mount passed to K3s via Balena. This critically prevents an overlay-in-overlay situation for K3s pods. While it’s possible to nest overlay filesystems in this way up to a hard limit of 2 levels, it adds nothing but complexity here.

For K3s, the runtime directory is in /run, which is typical, and the data directory defaults to /var/lib/rancher/k3s. Knowing this, we can construct our Balena app to have this configuration:

- tmpfs:

- /run

# This is usually symlinked, but symlink behavior can be odd when mounts are

# involved (citation needed), so we just additionally explicitly mount it here.

- /var/run

- volumes:

- k3s_datadir:/var/lib/rancher/k3s

Why not use the Balena socket?

Readers accustomed to Balena may be aware that it’s possible to add a special label to

your Balena app container to request that the balenaEngine socket be mounted inside

the container and its path stored in $DOCKER_HOST. It should theoretically be possible

for this to work by doing the following:

- At K3s kubelet container start, symlink the socket to /var/run/docker.sock, where K3s expects to find it (the path is not currently configurable.)

- Run K3s with the

--dockerflag to tell it to use a “dockershim” socket interface rather than the default containerd interface. Docker’s socket is not quite compatible with the K8s CRI (Container Runtime Interface), so K8s historically supported an adapter interface to bridge the gap (while this is officially deprecated, there should still be support for this method, albeit no longer by K8s core.)

There are two reasons I found for why this cannot work for K3s on Balena:

- Balena tries to bind-mount the socket at /run, which we already configured as a tmpfs mount. The mount gets screwed up b/c it’s trying to mount over this tmpfs.

- It turns out that when K3s uses the Docker driver it expects to be able to introspect the raw filesystem backing the container state. This appears to happen when it tries to allocate the container’s cgroup:

k3s E1213 01:22:12.729919 60 manager.go:1123] Failed to create existing container: /system.slice/docker-71d337540e5cd588869350a52a524e9b6e891cc6b5448011fd96a35c21d93530.scope: failed to identify the read-write layer ID for container "71d337540e5cd588869350a52a524e9b6e891cc6b5448011fd96a35c21d93530". - open /var/lib/docker/image/aufs/layerdb/mounts/71d337540e5cd588869350a52a524e9b6e891cc6b5448011fd96a35c21d93530/mount-id: no such file or directory

So K3s actually needs access to /var/lib/docker, which (a) does not exist for Balena (it is actually /var/lib/balena) and (b) cannot be bind-mounted as Balena does not support arbitrary bind-mounts from the host.

Consequences of NOT using the Balena socket

For our purposes, there are really not many benefits to re-using the Balena socket, except if it’s important that host bind-mounts be used: if K3s can’t spawn containers via the socket, it really has no way to provide bind-mounts from the host, because it does not have access to the host filesystem otherwise.

As already mentioned, Balena doesn’t support arbitrary bind-mounts from the host, so this is a moot point in this context. Device mounts (/dev) on the other hand should still work because our K3s container runs in privileged mode.

While Balena Engine has some nice features, like pulling container deltas and limiting memory usage during image pulls (to prevent page thrashing), containerd does a good enough job of replacing the other benefits of balenaEngine (small binary size and decompress-on-pull to avoid excessive disk i/o).

K3S cgroups on a systemd system

BalenaOS uses systemd as the init system (as do many[/most?] Linux distributions now.) This is important because systemd effectively takes control of cgroups itself and organizes them in a specific way. What is a cgroup?, you ask? It is just a way of letting “whoever is in charge” understand what system resources your process is allowed to consume; it is a way of ensuring the total load of the system is not exceeded, and enough headroom is given to this process or that.

K3s by default uses the “cgroupfs” cgroup driver instead, which manages cgroups via access to the /sys/fs filesystem.

Going down a rabbit hole

Under normal circumstances, using the cgroupfs driver in a systemd context means there are effectively two systems with different views of the total resource consumption on the system. My first thought was to try to configure K3s to use the systemd cgroup driver when running inside Balena. However, if you do some searching as I did, you will find this comment by a K3s maintainer, explaining why this is not possible:

systemd cgroup driver is not supported because systemd will not allow statically linked binaries (which k3s is built on). The cgroups manager code needs something from systemd CGO so we have to disable it.

I admit I still don’t really know how to parse this. systemd itself cannot (easily?) be statically linked due to some of its architectural dependencies. But it is not clear to me what cgo has to do with this.

In any event, as far as I can tell, the systemd cgroup driver does indeed work with

K3s, but it must be enabled on the K3s kubelet agent with

--kubelet-arg=cgroup-driver=systemd. Now, using this driver on the kubelet agent

(which, again, is running in our K3s container!) does come with a pretty harsh

consequence: we have to be running systemd in the container! Not only that, it needs

access to the D-Bus in order

to maintain some cohesion with the host systemd! Fortunately the latter can be done with

an additional Balena container

label. I

accomplished the former by stealing a lot of code from this example

project published by

Balena.

I was able to get K3s going, but there were still issues launching pods; it could not allocate the cgroup. After a lot of searching and debugging, I realized that actually, it worked fine to use the “cgroupfs” driver. But why?

Host OS systemd-cgls memory:

│ │ └─balena.service

│ │ ├─1804707 containerd

│ │ ├─1804896 /var/lib/rancher/k3s/data/86a8c46cd5fe617d1c1c90d80222fa4b7e04e7da9b3caace8af4daf90fc5a699/bin/containerd-shim->

│ │ ├─1806414 /var/lib/rancher/k3s/data/86a8c46cd5fe617d1c1c90d80222fa4b7e04e7da9b3caace8af4daf90fc5a699/bin/containerd-shim->

│ │ └─1806511 /var/lib/rancher/k3s/data/86a8c46cd5fe617d1c1c90d80222fa4b7e04e7da9b3caace8af4daf90fc5a699/bin/containerd-shim->

K3s container systemd-cgls memory:

└─balena.service

├─ 82 containerd

├─209 /var/lib/rancher/k3s/data/86a8c46cd5fe617d1c1c90d80222fa4b7e04e7da9b3caace8af4daf90fc5a699/bin/containerd-shim-runc-v2 -nam>

├─717 /var/lib/rancher/k3s/data/86a8c46cd5fe617d1c1c90d80222fa4b7e04e7da9b3caace8af4daf90fc5a699/bin/containerd-shim-runc-v2 -nam>

└─792 /var/lib/rancher/k3s/data/86a8c46cd5fe617d1c1c90d80222fa4b7e04e7da9b3caace8af4daf90fc5a699/bin/containerd-shim-runc-v2 -nam>

The pids are different but they are organized and visible in the same way, at least.

Solutions:

- Use the default “cgroupfs” driver for K3s, which will happily write to the unified cgroup it sees there. Systemd is OK with this.

- Set the limits on the K3s container as high as possible to give it the maximum amount of resources so it can pass those resources to pods.

- Do NOT bind-mount the /sys/fs filesystem into the container; this creates the “split-brain” situation between systemd and cgroupfs, and it seems there are some inconsistencies between the state of the filesystem. I think that /proc mounting is also required, and while this is possible in Balena, it adds additional problems, as systemd then sees that another systemd is running as the init process, etc. It’s just a mess this way.

Calico and FlexVol

What? We’re making this even more complicated? Well, yes. I wanted to run Calico as the CNI plugin to provide networking as opposed to the default flanneld plugin. I believe this is optional, though I did have some issues running flanneld due to the default MTU it tries to set on the interfaces it creates and manages (it is higher than the MTU on the interface Balena configures); this may be configurable in flanneld but I did not investigate, because I was interested in running Calico for the additional capabilities it can provide.

The main issue I encountered with Calico+K3s is that it uses a FlexVol driver, which is an earlier solution for the problem that was ultimately solved by the K8s CSI (Container Storage Interface.) FlexVols provide a general-purpose way to mount volumes into pods. Calico uses this mechanism to mount a socket into the pod, which is used to coordinate communication b/w the Calido DaemonSet and its node pod. To be honest, I am not quite sure exactly why this is needed, or what it does. But the main issue was that Calico needed to write this socket file to a place on the container’s filesystem, and that place was being bind-mounted from a different path inside the K3s container that was not backed by a Docker volume mount provided by Balena.

The solution is to create a volume mount just for this and tell Balena about it:

volumes:

# .. (other volumes)

- k3s_flexvol:/opt/libexec/kubernetes/kubelet-plugins/volume/exec

I also updated the K3s agent to point to this location instead of its default, rather

than tempting fate and trying to add the Docker volume at the default path:

--kubelet-arg=volume-plugin-dir=/opt/libexec/kubernetes/kubelet-plugins/volume/exec.

Another problem I encountered was that Calico by default, if you’re using their new “operator”-based deployment, will configure the CNI to use VxLAN for some pieces. IPIP is the usual default so I’m not sure why it changed in the operator migration, but I recall there were similar MTU issues with this setup. You can change this default by updating the Calico “installation” resource’s IPPools to use IPIP encapsulation, if you also encounter this (it’s supposed to be the default acording to the docs.)

Solutions:

- Add an additional volume mount for the FlexVol installation path and configure K3s to use it.

- Ensure the IPPools for Calico use IPIP encapsulation, or tweak flanneld’s MTUs to align with the values Balena configures on the host network links.

Cluster contextualization

As discussed, Balena’s deployment model assumes that a single application is deployed to all devices in a given fleet. Yet, in a K3s cluster, there are effectively two applications we need: one for the K3s API server, which drives the state of the cluster, and one for the kubelet agents, which create and manage the pods. A K3s cluster must initially start with an API server process. When the server bootstraps, it creates a node enrollment token, which the kubelets use to authorize themselves to join the cluster. This process of the cluster attaining this state, where the nodes have identified eachother and agreed on respective roles, is called contextualization.1

This could be done in any number of ways, but I wanted to see how much of this could reasonably be automated.

The approach I landed on leverages the fact that you can specify an additional label

io.balena.features.balena-api to have a Balena API token available in the container

environment. We can use this token to update device

variables to auto-configure the

cluster. It works like this:

First device enrollment: Device A is enrolled to the fleet; it is the first device.

The first application container to start is the k3s_context container, which runs a

script to determine what role the device will have. The script pulls a list of all

devices in the fleet. If it is the first device, it sets a device variable

K3S_ROLE=server on itself. The k3s_context container then goes into a wait loop,

where it periodically wakes up to see if the server has started properly. If so, it

writes two fleet device variables K3S_URL=... (which points to Device A’s IP) and

K3S_TOKEN=... (which has the value of the enroll token.) The enroll token is normally

written to disk by the k3s container to its data directory; because this is backed by

a Docker volume, we can share the volume with the context container, so it can read it

easily.

Subsequent device enrollment: Device B is enrolled to the fleet. Again, the context

container starts first. But, it sees that there is another device already in the fleet,

which means the server must exits. So it sets K3S_ROLE=agent on itself; the API server

URL and enroll token are already available to it because they are fleet variables, which

apply to all devices as defaults.

Concluding thoughts

Turns out, it’s indeed possible to run K3s on Balena! The container must be set up in a particular way such that it can provide filesystems properly to the pods launched there. More advanced CNIs like Calico can also be used. Overall, this combination has worked out well for me thusfar and I already have plans on extending the configuration to support more advanced networking capabilities. I have even been able to access peripherals such as the Raspberry Pi Camera Module from a pod launched on K3s this way. Pretty cool!

-

I have not seen this word used much, and I think Kate Keahey is the originator of its meaning. I haven’t found another word that describes this process. ↩